The Biological Clock and the Circadian Rhythm

Like the clock at home ticks, ticks it nowhere!

September 25, 2021

Abstract

Everything about the circadian rhythm, chronobiology, and why it's important to align your social and biological clocks.

Date

September 25, 2021

Time

12:00 AM

Photo by Abdul on Unsplash.

Photo by Abdul on Unsplash.

What is a biological clock?

A biological clock is an internal timing mechanism that regulates the rhythmic occurrence of various processes within plants, animals and humans. The sleep-wake cycle, the female menstrual cycle, bird migration or the mating behavior of animals are all examples of daily, monthly, annual or seasonal rhythms. A circadian rhythm, from the Latin circa and dies (meaning about and day), is a rhythm of about 24 hours. A crucial feature of a biological clock and the circadian rhythm is that the rhythm continues even if there is no (external) notion of time.

The first discoveries

The difference between this internal and external regulation was first described by Jean Jacques d’Ortous de Mairan. In the 18th century, the French mathematician and astronomer was intrigued by the opening and folding of the leaves of his mimosa plants with the rising and setting of the sun. When he placed the plants in a dark closet, he discovered that the plants, even in the absence of sun light, kept opening and folding with the same daily rhythm.

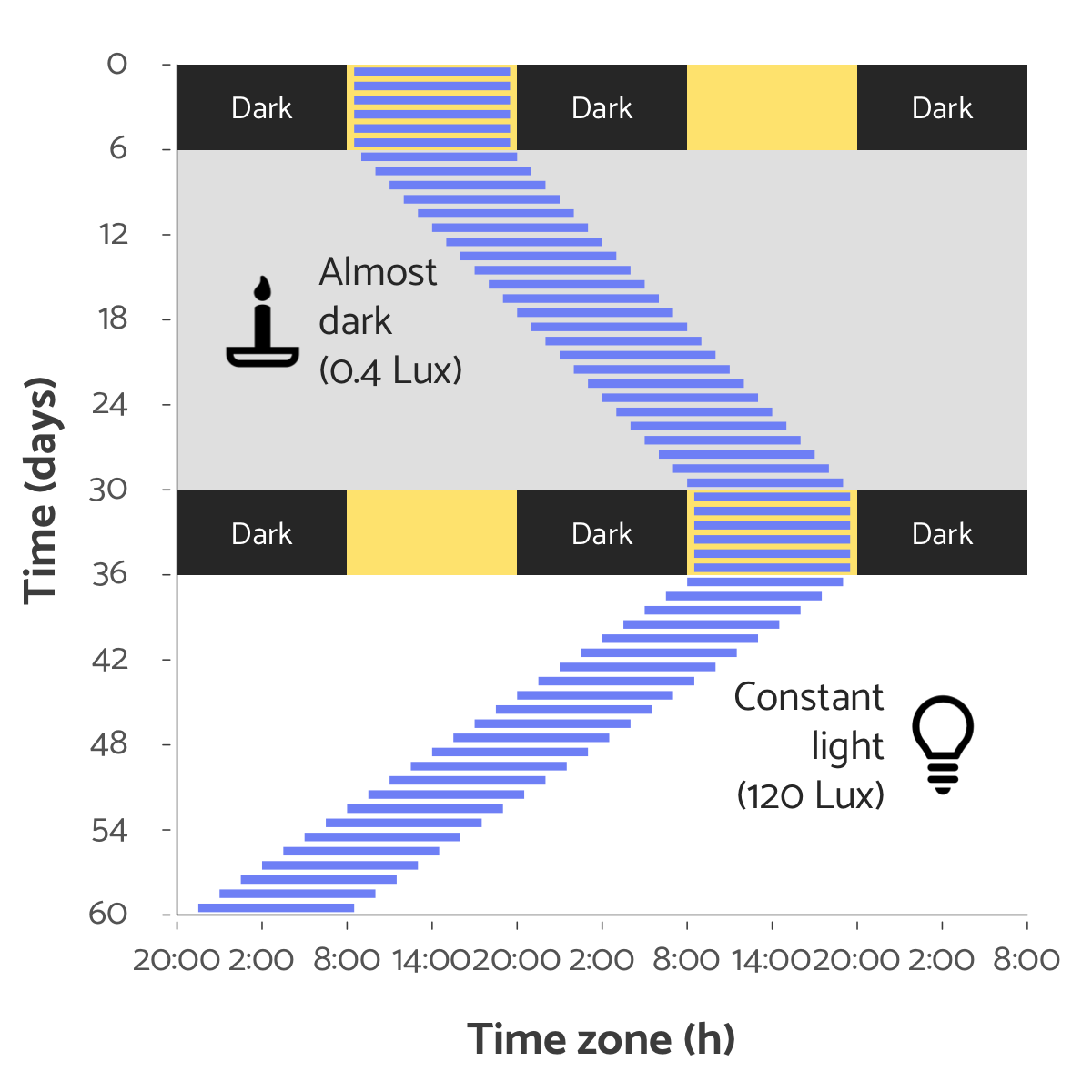

A similar external regulation was demonstrated in animals that were kept in either a lit or darkened room. While their activity patterns showed a very constant rhythm, the time at which the animals were active moved to an earlier or later time every day (Figure 1). This circadian rhythm has also been demonstrated in man [1]. In 1962, the French geologist Michel Siffre stayed in an underground cave without any sunlight, trying to record the time of day. Even though Siffre thought he had spend 37 nights underground instead of the 62 nights that had actually passed, the times at which he had dinner, went to bed and woke up showed that his biological clock kept working with a regular rhythm of about 24 hours.

Chronobiology: the study of circadian rhythms

Although the existence of a biological clock was known for a while, the exact working has only been revealed over the past decades. In 2017, the Nobel prize for physiology or medicine was awarded to three chronobiologists for their work on circadian rhythms. The researchers had discovered the so-called clock genes (with names as period, timeless, and doubletime) that are involved in the regulation of the biological clock.

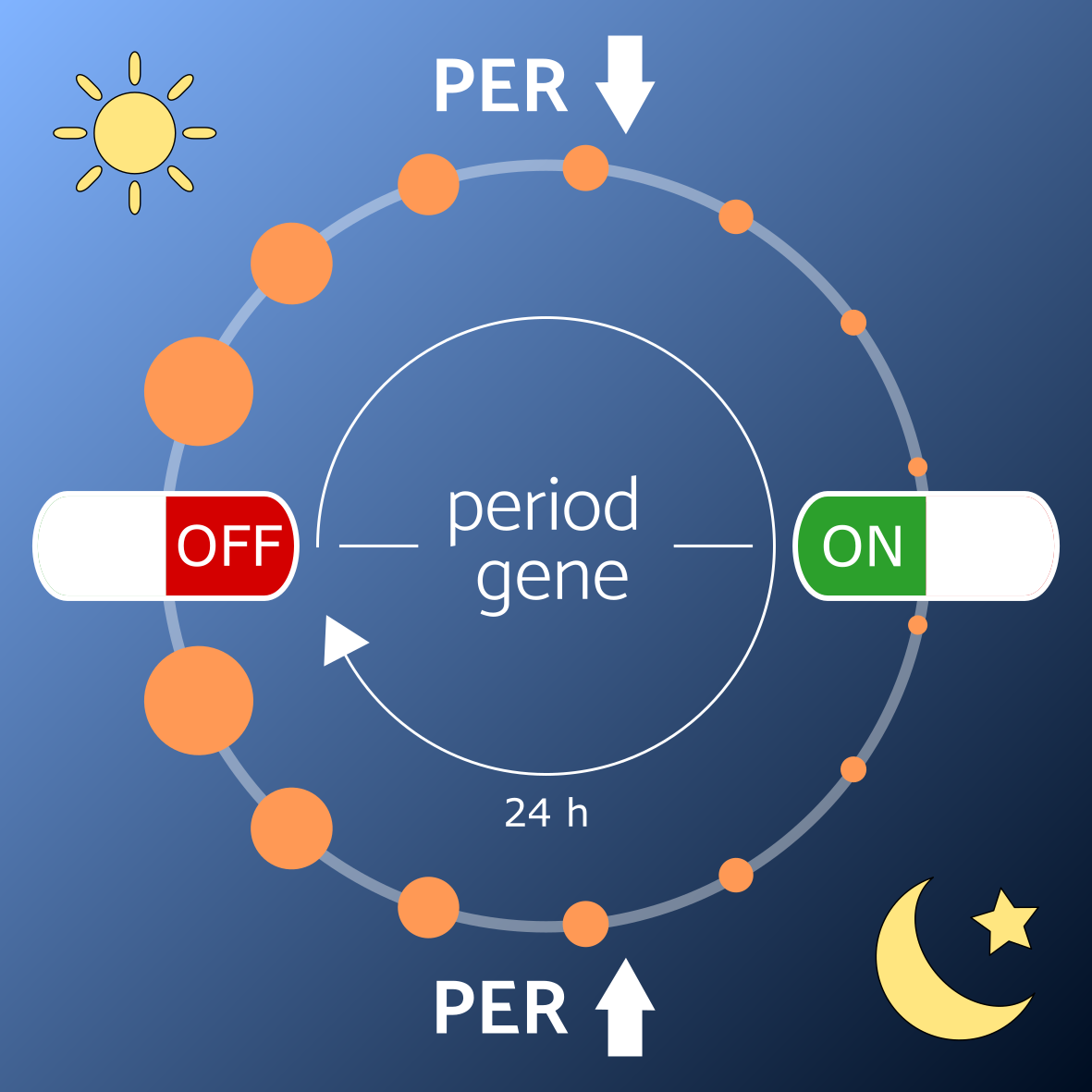

One of those clock genes, the period gene, is turned on during the night, resulting in the production and accumulation of PER protein. This accumulated PER protein then turns off the period gene, inhibiting its own production during the day. When, at the end of the day, the amount of PER protein has lowered sufficiently, the period gene is activated again. The fluctuation in PER protein (Figure 2) occurs with a rhythm of about 24 hours [2]. Fruit flies with a period gene cycle shorter than 24 hours showed a sleep-wake cycle that was also shorter than 24 hours. If the period gene was, on the other hand, completely turned off, fruit flies would lose all notion of time and fall asleep at random hours.

The master clock and the peripheral clocks

It was initially thought that there was one biological clock that regulates all circadian rhythms. But when researchers removed the eyes from a frog and kept the eyes artificially alive, they discovered that, even without any connection to the brain, the frog’s eyes were still producing the sleep-wake hormone melatonin with a 24 hour rhythm. Other researchers observed the same phenomenon in fruit flies in which the period gene was modified in such a way that light is emitted when the period gene is turned on. Surprisingly, when body parts were removed from the fruit flies, they would continue to glow and dim according to a 24 hour rhythm!

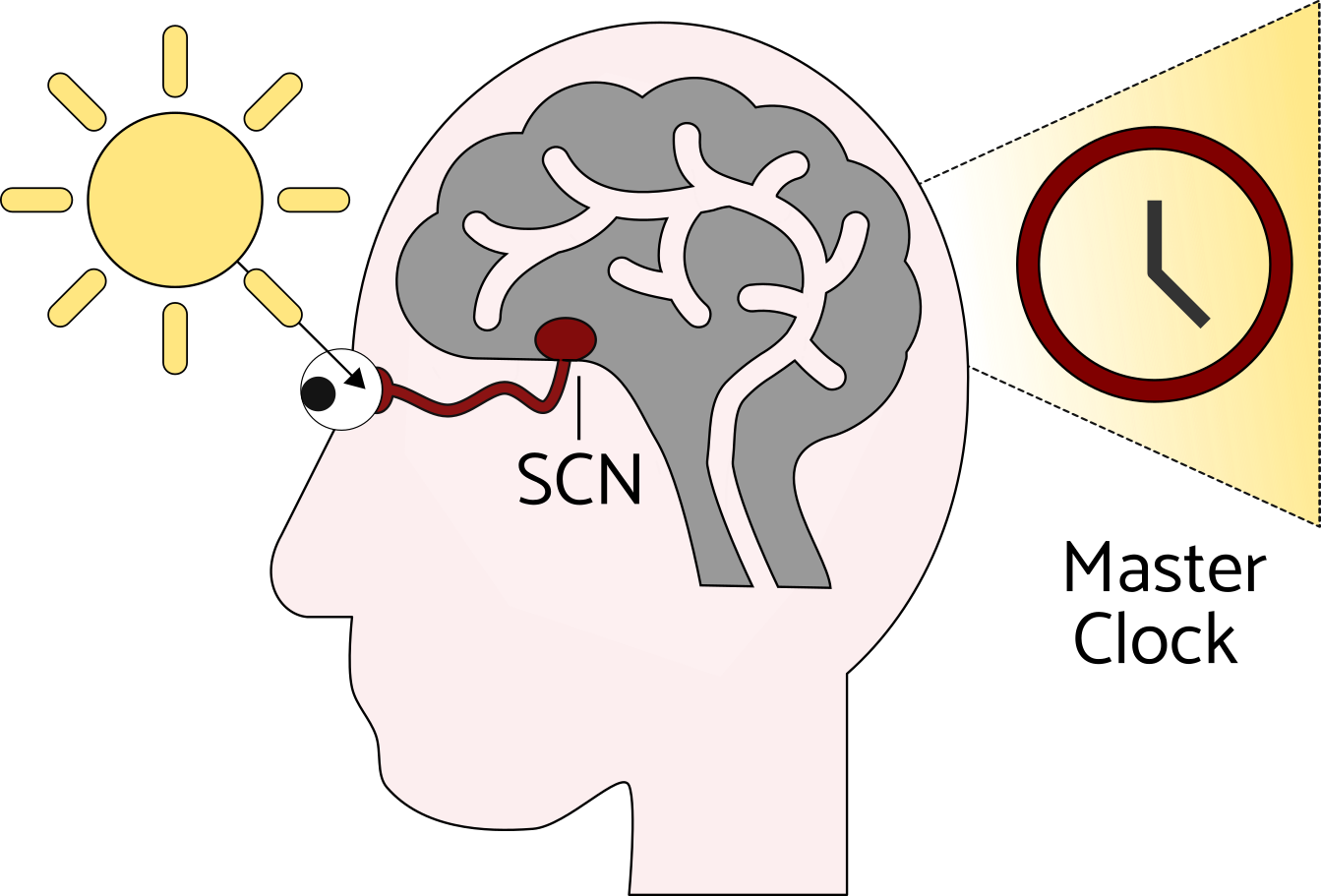

We now know that nearly every cell, organ and tissue contains its own biological clocks, which are synchronized to our 24 hour day-night rhythm by the so-called master clock located in the suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN) in the brain (Figure 3). The SCN consists of about 20,000 nerve cells. That sounds like a lot, but the SCN is a remarkable tiny and highly efficient network of nerve cells that, through its central position, connects the eyes with the brain. In this way, light cues from the environment enable the master clock to coordinate the daily rhythms that, in turn, synchronize the peripheral clocks.

It has long remained unknown how the light cues were actually transmitted to the master clock. At the turn of the century, chronobiologists discovered a new type of light receptors in the human eye. These retinal ganglion cells are especially sensitive to blue light and enable direct communication from the eye to the master clock.

Zeitgebers

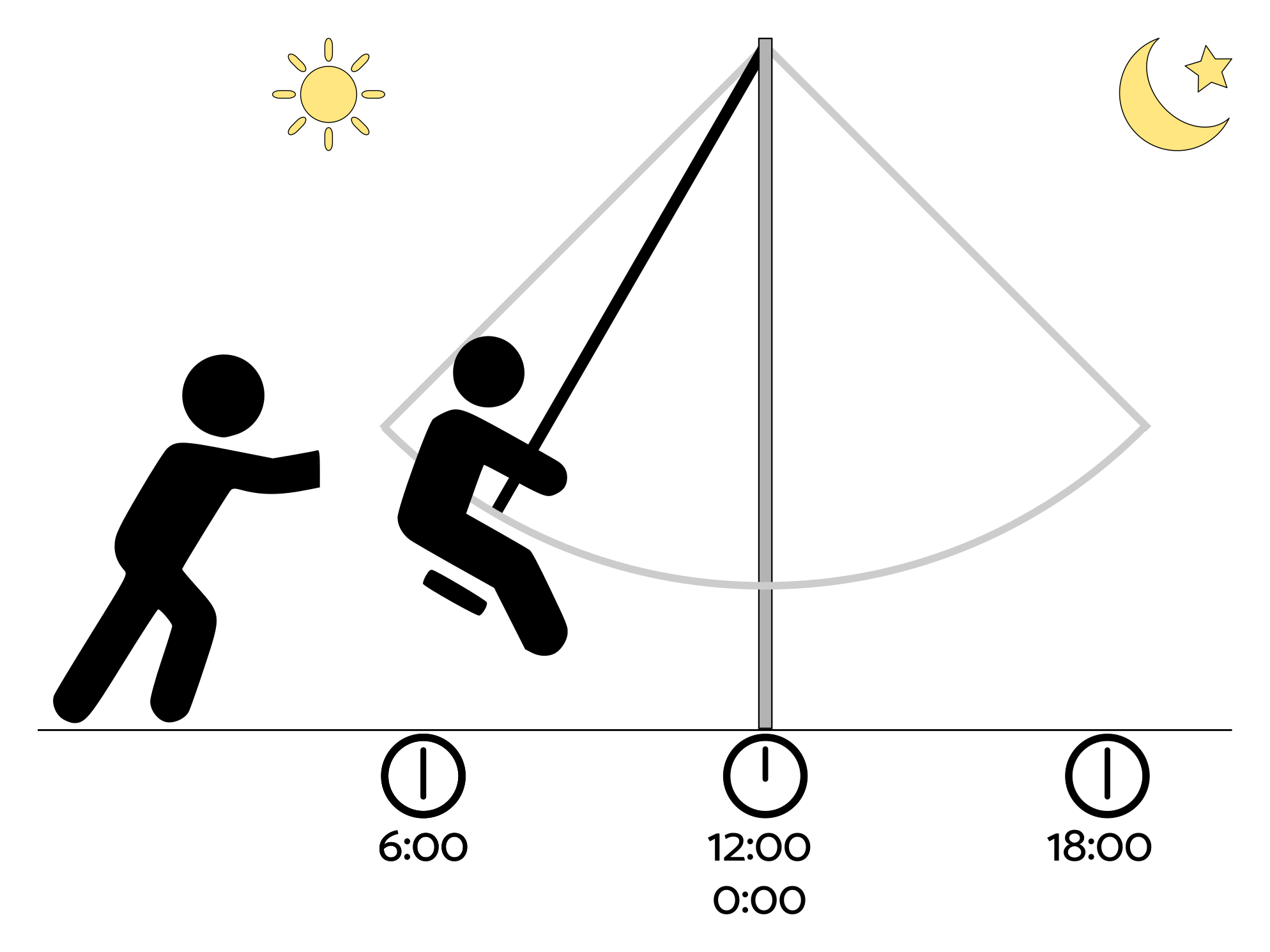

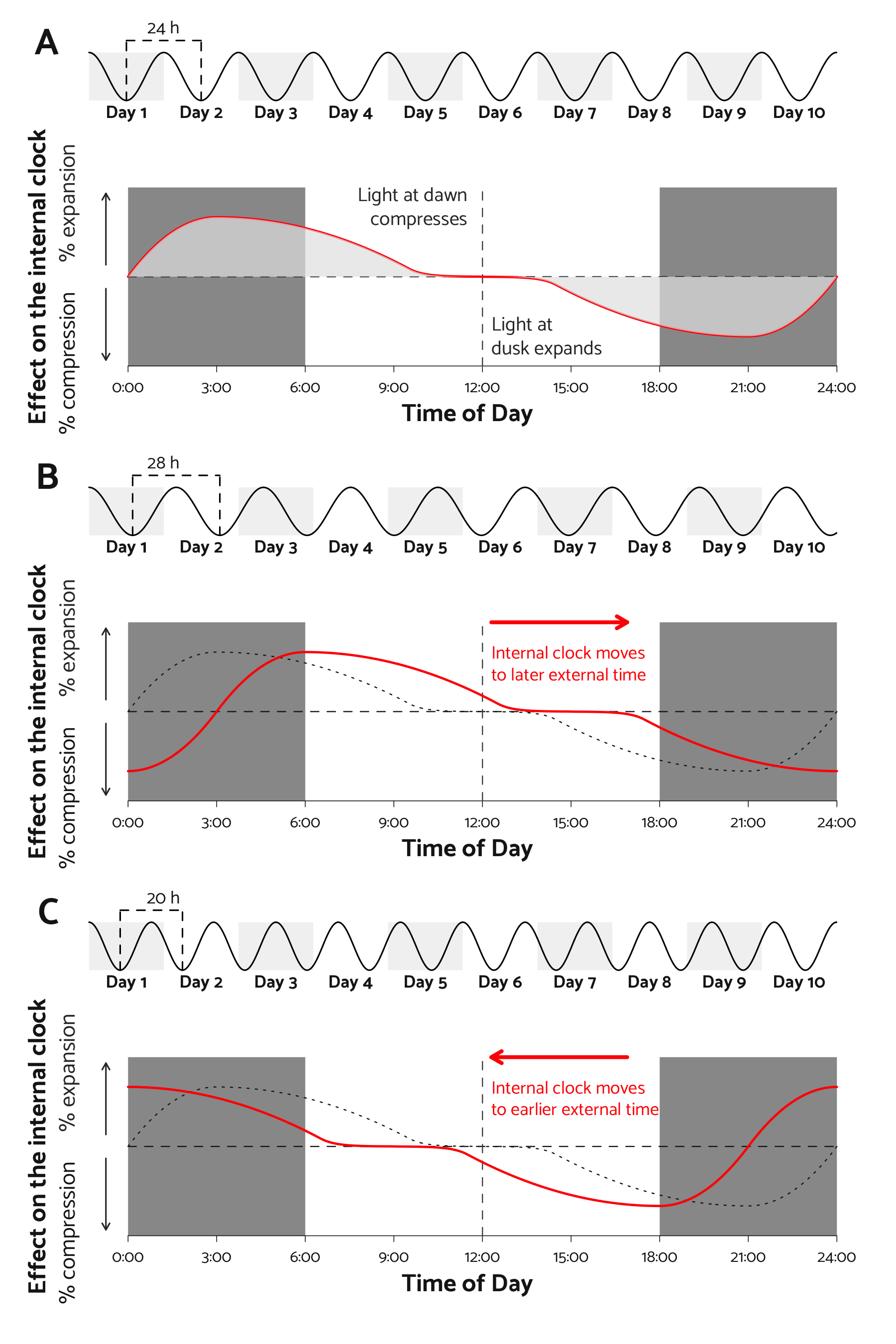

How can the internal circadian rhythm be adjusted to the period of another rhythm, our 24 hour day-night cycle? The process to make the internal clock fit the external day-night rhythm is called entrainment and occurs based on time cues or zeitgebers. Imagine the biological clock as a swing moving back and forth from morning to evening. The swing has its own internal rhythm of about a day. The zeitgeber can be seen as the person pushing the swing to adjust its rhythm to follow exactly 24 hours. The effect on the swing’s rhythm will depend on when the swing is pushed: if pushed while moving away, the swing will speed up; if pushed while moving toward the zeitgeber, the swing will slow down (Figure 4).

Entrainment

When thinking of light as the zeitgeber or pusher of the swing (Figure 4), light (or a push) in the morning will speed up the internal rhythm and compresses the length of the internal day, whereas light (or a push) in the evening slows down the internal rhythm and expands the length of the internal day. This synchronisation of the internal rhythm to our 24 hour day-night rhythm, however, has its consequences.

For example, the internal clock in people with an internal rhythm longer than 24 hours needs to be compressed to be in sync with a 24 hour rhythm. To catch more of the compressing early morning light and less of the expanding evening light, their internal clocks will move to a later external time (Figure 5B). Consequently, people with a circadian rhythm longer than 24 hours, will tend to wake up and go to bed later, whereas people with a circadian rhythm shorter than 24 hours, will tend to wake up and go to bed earlier (Figure 5C).

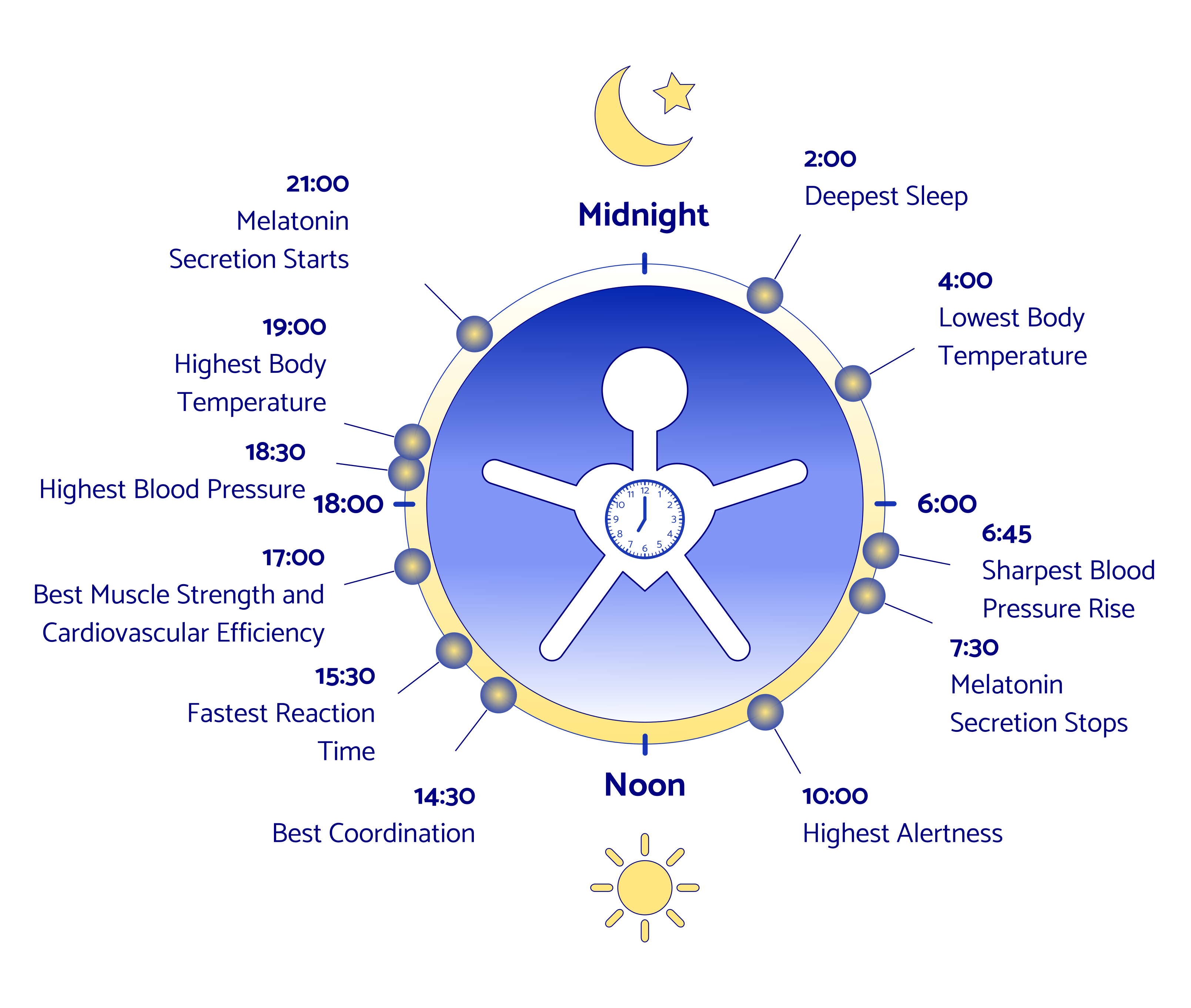

The hand of the clock

The constant synchronization of the biological clock makes that we can adapt to new time zones, for example after an overseas trip or when changing to daylight savings time. The experiment in Figure 1 already showed that the deregulated sleep-wake rhythm in test animals could be easily recovered after entraining to a 24-hour day-light rhythm. Daylight, and other zeitgebers, trigger the start of various daily rhythms in the master clock in the SCN. One of those daily rhythms is the release of the hormone melatonin, therefore named the hand of the clock. Melatonin induces sleepiness and plays a crucial role in our sleep-wake rhythm. Besides the sleep-wake rhythm, various other daily rhythms (Figure 6) are regulated by the master clock such as our body temperature or blood pressure. These daily rhythms on their turn play support the synchronization of the peripheral biological clocks.

Social Jetlag

Our body is at its best when the peripheral clocks are aligned with the master clock. The most important zeitgeber to support the synchronization of the master clock is light. Besides light, also the times at which you eat, sleep or exercise can help synchronize the biological clock. But be aware: the same factors can also deregulate your biological clock! A disturbed sleep-wake rhythm, e.g., as a result of a night shift or jetlag, but also eating at irregular hours can deregulate the peripheral clocks and have a negative effect on your focus, appetite, feelings or performance. You may recognize this feeling, a so-called social jetlag, from a Monday morning when you have to wake up early for work after having slept in during the weekend. When the peripheral clocks are de-synchronized for too long, this can even lead to health issues. So for a healthy and vital life, you’d better keep your social and biological clocks aligned!

References

- Aschoff J., Circadian Rhythms in Man, Science , 148: 1427-32 (1965).

- Press release Nobel prize committee, read on Jan 29 2020.

- Roenneberg T., Daan S, Merrow M., The art of entrainment, Journal of Biological Rhytms, 18: 183-94 (2003).

- Roenneberg T., Internal Time: chronotypes, social jet lag and why you’re so tired. Harvard University Press (2012).

- Smolensky M., Lamberg L., The body clock guide to better health: how to use your body’s natural clock to fight illness and achieve maximum health. Henry Holt and Co (March 2015).

- Posted on:

- September 25, 2021

- Length:

- 9 minute read, 1832 words

- Categories:

- Body Health & Science

- See Also: